Recasting Bangladesh’s maritime destiny

Bangladesh’s future is no longer tethered solely to its fields and factories. Its sovereignty, security, and strategic relevance now depend on its ability to govern, command and compete at sea, writes Abdul Monaiem Kudrot Ullah [Source : New age, 20 August 2025]

AT THIS decisive moment in Bangladesh’s strategic course, a new vector has been set — one not drawn on land, but charted across the sea. In a nationally televised address, chief adviser Dr Muhammad Yunus signalled a maritime turn of historic magnitude. His proposition — that Bangladesh will ‘make the world our neighbour’ by turning decisively towards the sea — is not mere rhetorical drift. It is a call to sail.

To those of us commissioned in salt and steel, whose service has been shaped by tides, hulls and charts, this is not a sentimental resurgence. It is a professional imperative. Like a ship long moored, the maritime vision of the nation is preparing to weigh anchor. The challenge ahead is not abstract — it is navigational, operational and institutional.

Language matters. Maritime strategy begins not with ships, but with ideas. As maritime theorist Christian Bueger reminds us, words are vessels — they structure maritime governance, shape public legitimacy and signal intent to allies and adversaries alike. When a head of government invokes the sea as the locus of national destiny, a doctrinal window opens. The question is whether we are ready to sail through it.

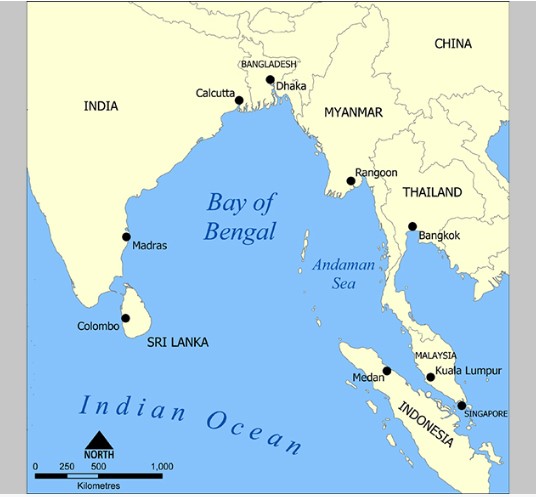

No longer can Bangladesh be defined as a landlocked mindset flanked by rivers. It is, by virtue of geography and destiny, a rimland state. This realignment echoes Nicholas Spykman’s seminal thesis: that the stability — and influence — of the Rimland determines the balance of power in Eurasia and beyond. The Bay of Bengal is no longer a peripheral basin. It is a strategic corridor — a forward-operating environment where regional currents meet global designs.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, India’s Act East Policy, and the US-led Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy all intersect in these waters. This convergence does not wait for our readiness. If Bangladesh wishes to remain relevant in the evolving Indo-Pacific order, maritime power is not a luxury. It is a strategic necessity.

Encouragingly, this shift is beginning to surface in the national political theatre. The newly formed National Citizen Party (NCP) has included a maritime directive in its 24-point ‘New Bangladesh’ platform. Point 17, under the banner of Climate Resilience and River and Ocean Protection, goes beyond coastal tokenism. It recognises ocean governance not as an environmental afterthought but as an extension of sovereignty, economic posture and strategic depth. Port infrastructure, fisheries governance riverine logistics — these are not departmental tasks, but components of a national maritime doctrine.

By contrast, established parties such as the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and Jamaat-e-Islami remain adrift in this domain. Their platforms, while detailing judicial reform and democratic norms, are charted with terrestrial eyes. The absence of a maritime clause is more than an oversight — it is a strategic vacuum. In an era where the maritime domain defines the velocity of trade, diplomacy and deterrence, this omission risks political irrelevance.

The Bay is no longer a line on a map — it is a theatre of governance, a fulcrum of resilience and a test of inter-agency alignment. The Navy’s role is central — not just in force projection, but in building a national sea culture, coordinating with civilian ministries and defining the contours of maritime law and environmental stewardship.

This is a moment for the Bangladesh Navy to assume not just operational, but doctrinal leadership. It must lead the maritime conversation, not follow it. It must shape the national understanding of maritime security — not merely defend it.

If Dr Yunus’s address is to catalyse a realignment in national posture, then its trajectory depends on more than oratory. It demands institutional readiness, political consensus and above all, maritime command culture — a culture that sees the Bay of Bengal not as a boundary to be guarded, but as an operational environment to be governed, explored and led.

Bangladesh’s future is no longer tethered solely to its fields and factories. Its sovereignty, security, and strategic relevance now depend on its ability to govern, command and compete at sea. The sea is not a frontier — it is the fleet’s new home.

The Bay is our frontline

STRETCHING across the Indo-Pacific arc, the Bay of Bengal no longer sits on the margins of global strategy — it has become a dynamic node of power projection, logistics competition and normative contestation. What once appeared a maritime cul-de-sac has emerged as a critical corridor connecting South and Southeast Asia, linking India’s vast coastlines with Myanmar’s vulnerable delta, Thailand’s strategic straits and Bangladesh’s own newly delimited maritime space.

With more than half of global container traffic transiting through the broader Indo-Pacific, the Bay’s centrality is sharpening — not just for trade, but for surveillance, signalling and presence. This is no longer a backwater. It is the soft underbelly of strategic rivalry. And Bangladesh, positioned at this pivot, must decide whether to drift as an observer — or to navigate as a stakeholder.

The Rimland revisited

NICHOLAS Spykman’s insight into the geopolitical primacy of coastal regions — the ‘rimlands’ — remains strikingly relevant. Far from being buffers, these zones are decisive theatres where land meets sea, where ports become policy and where control generates influence. His warning that the power controlling the rimland controls Eurasia is playing out visibly across the Bay: from China’s infrastructure push in Kyaukphyu and Hambantota, to its underwater diplomacy via submarine visits, the contest is both overt and methodical.

For Bangladesh, this is not a theoretical proposition — it is an operational dilemma. The nation now sits in a maritime zone defined not only by transit but by tension. To ignore Spykman’s logic is to misread the strategic gravity accumulating along our shores.

Geography is strategy

BANGLADESH’S geography grants it access, leverage and responsibility. Its riverine arteries flow into the Bay, offering a logistics ecosystem few can replicate. But strategic geography without strategic governance is vulnerability masquerading as potential. The challenge lies in converting locational advantage into structured influence.

This demands more than port expansion or coast guard patrols. It requires an integrated strategy that fuses infrastructure with policy, deterrence with diplomacy and national ambition with regional stewardship. Maritime strategy cannot be reactive — it must be anticipatory, layered and anchored in sovereign capacity.

Bangladesh’s southern frontier — where shallow riverine deltas meet the deep waters of the Bay — offers more than a picturesque coastline; it presents a rare strategic geography. This amphibious terrain enables a uniquely hybrid logistics ecology, linking inland waterways, rail networks, roads and ports into a potential multimodal grid. But potential alone is not power. Without deliberate integration, this geography remains underutilised, vulnerable to fragmentation and foreign leverage.

Bangladesh is neither landlocked nor fully littoral — it is a hybrid state. Its riverine arteries reach deep into the heartland, providing natural conduits to the sea. Yet its ports often function as isolated terminals rather than integrated nodes. This must change. Maritime power today, as port governance scholars like Theo Notteboom argue, lies not in raw throughput, but in logistics intelligence — the ability to orchestrate flows across domains and across borders.

A coherent national connectivity strategy must therefore replace the current patchwork of standalone projects. Roads must lead to rails that link to rivers that flow into ports — with all systems designed not only for cargo, but for national resilience. This demands transparent governance, environmental foresight, and above all, rejection of opaque, exclusivist foreign infrastructure deals that offer visibility but undermine viability.

Strategic autonomy is not declared — it is designed. And it begins by turning Bangladesh’s hybrid geography into an integrated system of functional corridors. In this, the Bay of Bengal is not the endpoint of national ambition — it is the launchpad.

Reframing the navy: beyond coastal security

The Bangladesh Navy can no longer be confined to a defensive or ceremonial identity. Traditionally regarded as a coastal guard, its remit must evolve in light of shifting maritime dynamics and expanding national interests. As the Bay of Bengal emerges as a strategic theatre in the Indo-Pacific, the navy must transition into a multidimensional actor responsible not only for territorial defence but also for maritime governance, regional diplomacy and strategic deterrence.

This evolution is not optional. Non-traditional threats such as illegal fishing, transnational crime, ecological degradation and cyber vulnerabilities increasingly manifest at sea. The navy’s role must now encompass law enforcement, resource security, environmental stewardship and regional norm-shaping.

The central challenge lies in moving from symbolic posturing to sustained operational presence. Strategic relevance is determined not by ceremonial visibility but by endurance, readiness and multi-theatre capability. This transition requires:

Integrated maritime domain awareness: Establishing a real-time surveillance grid combining satellite data, UAVs, coastal radar, and civil-military sensor networks. Maritime domain awareness is the backbone of maritime situational awareness.

Resilient naval logistics: A robust logistics architecture is essential to sustain presence. This includes forward-operating bases, digitalized fleet management, and adaptable supply chains tailored to the Bay’s climatic and geographic variability.

Smart acquisition: Platform selection must prioritise mission fit, sustainability, and lifecycle cost. Offshore patrol vessels, maritime patrol aircraft, and hybrid-capable corvettes/frigates should dominate procurement over prestige-driven acquisitions.

Cybersecurity integration: As ports and naval systems become increasingly digital, cyber resilience becomes a frontline requirement. Naval C4ISR systems and maritime infrastructure must be hardened against cyber threats.

Amphibious-riverine synergy: Given Bangladesh’s deltaic geography, the Bangladesh Navy must maintain dual-domain capabilities: enforcing sea control while operating effectively in riverine environments.

Operationalising sovereignty

FOLLOWING the legal resolution of maritime boundaries, the focus must now shift to enforcement. Operational sovereignty requires persistent presence and credible capability across the exclusive economic zone and key sea lines of communication. Key roles include:

Resource protection: Patrolling and defending offshore energy installations, fisheries, and undersea minerals.

Trade security: Safeguarding port access and ensuring uninterrupted maritime trade.

Delta defence: Integrating coastal and riverine operations to secure the amphibious frontier.

Strategic framework

NICHOLAS Spykman’s rimland theory, which highlights the strategic centrality of coastal states, is directly applicable to Bangladesh. The Bay of Bengal is not a peripheral zone — it is the new theatre of competition and connectivity. To function effectively as a rimland power, Bangladesh must develop: layered maritime infrastructure, persistent surveillance and patrolling and regional naval interoperability and crisis-response capability.

Calls for a ‘Blue Economy’ and maritime awakening are no longer sufficient. Institutional maturity must underpin strategic vision. This requires:

Doctrinal alignment: Operational planning and force structures must reflect realistic strategic objectives, not abstract ambitions.

Systemic investment: Investment in surveillance, maritime infrastructure, and logistics must be coordinated and scalable.

Capability over symbolism: Acquisitions must be driven by function and mission relevance, not fleet prestige.

Force design and institutional integration

The Bangladesh Navy’s future force structure must reflect its dual operating environment — open sea and riverine terrain. This entails modular, mission-specific platforms; persistent ISR systems networked through an integrated MDA grid and C4ISR infrastructure tailored for hybrid threats and contested domains

Moreover, true maritime effectiveness lies in the Navy’s ability to collaborate across civilian agencies, integrate with national policy and operate in joint task force structures.

Operational endurance cannot rely on hardware alone. Logistics is the strategic enabler of presence and persistence. The Bay’s dispersed geography and climate volatility demand prepositioned supply hubs and repair facilities, real-time digital logistics monitoring and cyber-protected infrastructure and redundancy systems.

Civil-military convergence: beyond coordination

BANGLADESH’S maritime strategy demands more than isolated policy interventions. It requires institutional convergence — an integrated civil-military doctrine that aligns economic, environmental and security imperatives. Without this synthesis, strategic fragmentation is inevitable. The absence of a cohesive framework linking naval presence to commercial ambition and foreign policy undermines strategic resilience. A Joint Civil-Military Maritime Doctrine, codified through executive authority or legislation, is essential to bridge this divide. It must address both conventional threats and hybrid challenges such as IUU fishing, cyber sabotage, and disaster response.

Institutional anchoring

STRATEGIC foresight must be institutional, not episodic. Establishing an autonomous Maritime Coordination Authority — professionally staffed and politically insulated — would provide continuity across electoral cycles and bureaucratic reshuffles. Its mandate would include harmonising naval strategy with blue economy goals, environmental sustainability and diplomatic engagement. Such an institution would transform maritime governance from a reactive process into a proactive capability.

Strategic autonomy in a contested Indo-Pacific

IN THE intricate theatre of the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh finds itself increasingly courted by external powers — China, India, Japan, the United States, and key ASEAN states — all seeking strategic footholds. Yet, few of these overtures are without self-interest. In the spirit of James Cable’s ‘constructive engagement’ and ‘limited liability’ diplomacy, Bangladesh must approach these alignments with a deliberate blend of prudence and principle.

Strategic partnerships should not evolve into strategic liabilities. Reciprocity — not reliance — must define external cooperation. Engagements must enhance flexibility and safeguard sovereign choice, rather than bind Bangladesh to external strategic agendas.

Multilateral platforms such as IORA, BIMSTEC, and ReCAAP offer arenas where Bangladesh can project influence without succumbing to security patronage. Involvement in these forums must go beyond attendance. It should entail agenda-setting — shaping maritime norms, fostering capacity-building and reinforcing collective security through diplomatic presence.

In line with Cable’s concept of ‘soft naval power’, Bangladesh’s naval diplomacy must prioritise quiet credibility over flamboyant display. Port visits and joint drills have their role, but maritime influence is forged through continuity of presence, competence in responding to contingencies and genuine collaboration with regional navies.

Maritime engagement should serve as a vector of influence — not submission. Assistance — be it technical, financial or operational — must be critically filtered through national imperatives. The Bangladesh Navy’s diplomatic posture should be that of a confident actor: cooperative, yet never compromised; open, yet never overextended.

In a contested Indo-Pacific, strategy lies not in choosing sides but in shaping space — defining one’s role through capability, coherence and quiet resolve.

Governance as maritime power

IN THE maritime domain, influence is not merely the outcome of displacement tonnage or fleet size — it is a reflection of governance. As Dr Joshua Tallis has persuasively argued, maritime security begins not at sea, but in institutions. Bangladesh’s maritime strategy must therefore treat governance not as a complement to power, but as a foundation of it. The blue economy — promising returns in fisheries, offshore hydrocarbons and transit trade — is security-sensitive and logistics-intensive. Without systemic regulation and infrastructural integrity, development remains theoretical.

Port infrastructure should not be a disconnected economic initiative; it must be embedded within broader governance architecture. This includes:

Rigorous enforcement mechanisms against illegal fishing and marine pollution

Mandatory ecological audits in port construction and dredging projects

Transparent revenue frameworks and blue economy oversight

Flag-state accountability through vessel registration and tracking

Maritime security as an economic enabler

Naval infrastructure investment must be reframed — from traditional defence budgeting to capability-based governance. Bangladesh’s exclusive economic zone holds not just resources but vulnerabilities. Securing that space — from maritime trafficking to potential geo-economic disruptions — is a prerequisite for realising the country’s economic future. Tallis’s maritime realism echoes Spykman’s theory: geography may define opportunity, but governance determines outcomes. Trade security, infrastructure resilience, and integrated maritime-riverine logistics must now be core naval competencies.

Infrastructure projects — Matarbari, Payra, and others — are only strategic if they enhance national leverage. The source of financing should never dictate operational control. Bangladesh must approach external engagement through diversified partnerships rooted in utility, not alignment. Dr Tallis’s emphasis on functional realism is instructive here: influence grows from institutional capacity, not ideological camp-following. Hedging isn’t avoidance — it’s prudence.

Architecture of convergence

BANGLADESH’S geography — neither fully continental nor entirely littoral — offers a rare hybrid identity. But hybrid geography demands hybrid strategy. Bangladesh must evolve a connectivity doctrine that integrates road, rail, river, and sea into a unified operational grid. Maritime infrastructure should serve national coherence, not foreign visibility. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a reminder: logistics are power and power is political. National autonomy will depend not on isolation, but on infrastructural and institutional self-possession.

Strategic insight is abundant; execution is the real deficit. The Bay of Bengal is no longer an overlooked corner — it is a contested commons. Presence alone is insufficient. Bangladesh’s response must be institutional, deliberate, and sustained. That requires a joint maritime doctrine that binds civil-military interests, a dedicated maritime coordination authority to synchronise policy, and resilient institutions with continuity beyond electoral cycles.

As Dr Tallis suggests, modern maritime competition is defined less by great power posturing than by the effectiveness of governance frameworks. Bangladesh must stop reacting to the region’s tempo and start shaping it.

Choosing the Bay, choosing Bangladesh

IN THIS epoch of oceanic ambition, the very notion of Bangladesh’s future is being recast upon the waters of the Bay of Bengal. The sea — once dismissed as a periphery — is now the fulcrum of national survival. To ignore it is not just strategic negligence; it is a forfeiture of sovereignty itself.

For too long, our mainstream political discourse has remained strikingly landlocked. The legacy parties have largely failed to articulate a vision for maritime governance, let alone recognise the Bay as a domain of strategic consequence. This maritime blindness has left critical national interests adrift, outsourced to bureaucratic inertia or transactional foreign deals. In contrast, the newly formed National Citizens Party has made a meaningful break from this pattern by embedding maritime strategy into its founding charter. In doing so, it signals a long-overdue recognition that Bangladesh’s future lies not just on land, but in the currents of the Bay.

The Bangladesh Navy, long framed as a coastal sentry, must now be understood as a sovereign tool of governance. This is not mission creep — it is mission clarity. Its evolving role — from defending maritime boundaries to enforcing ecological regulation and anchoring regional norms — must be institutionalised, not improvised. This is no longer an operational question; it is a national mandate.

Spykman’s Rimland thesis reminds us with sharp clarity: littoral states influence regional order. Bangladesh, straddling the hinge of South and Southeast Asia, is neither peripheral nor passive. Its maritime posture must be driven by foresight, not reaction — by doctrinal vision, not borrowed templates.

The alliances on offer — from Indo-Pacific Quad players to Chinese-led corridors — are not philanthropic overtures. They are interest-driven architectures. Bangladesh must engage them on terms defined by sovereignty, not subordination. Platforms like IORA and BIMSTEC must cease being ceremonial affiliations; they should become stages where Dhaka sets agendas, not simply reacts to them.

The blue economy is not a commercial side note. It is a logistics- and governance-intensive enterprise, where power is expressed through regulation, infrastructure, and ecological intelligence. A coherent maritime strategy must dissolve the artificial silos between ministries and security agencies, binding riverine networks, coastal ports and high-seas governance into a seamless operational vision.

Bangladesh’s rivers, coasts, and corridors are not borders — they are bridges. Choosing the Bay is choosing governance over gesturing, foresight over forgetfulness. In doing so, and with political platforms like the NCP finally giving it voice, Bangladesh chooses a future it has authored, not inherited.

Abdul Monaiem Kudrot Ullah, a retired captain of the Bangladesh navy, is an informed voice on institutional reform, geo-strategy, strategic governance and supply chain management.