TWIN TRAP : Poverty and corruption

Abdullah A Dewan [Source: New age, 20 December 2025]

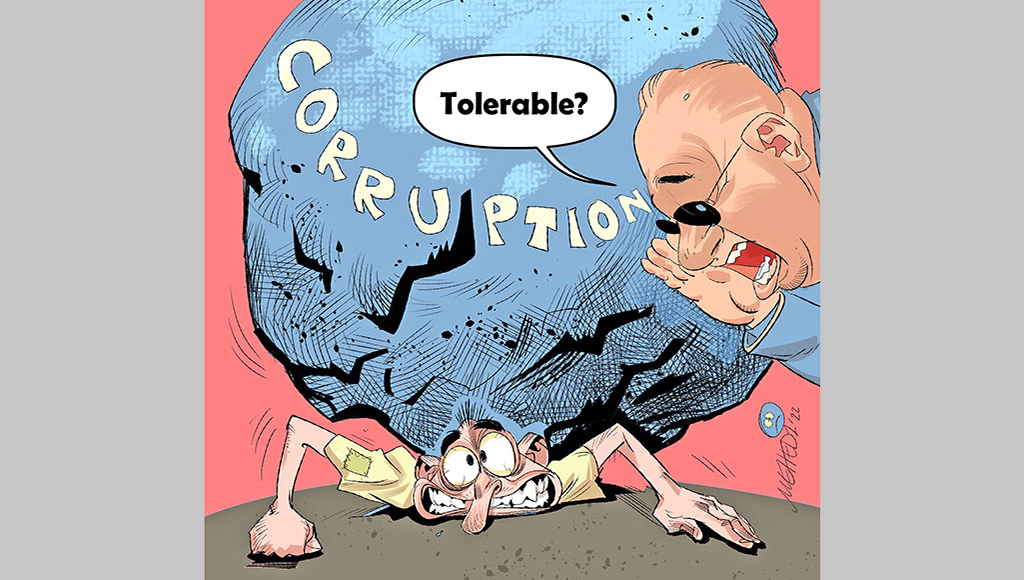

BANGLADESH today stands trapped inside two interconnected circles, poverty and corruption, like a nation caught on a spinning, grinding wheel. One suffocates households from below, the other hollows out institutions from above; one deprives citizens of nutrition, education, mobility and hope, while the other deprives the state of leadership, trust and moral legitimacy. These are not separate problems running side by side, they mesh like interlocking gears. Poverty breeds vulnerability, corruption breeds impunity, and together they form a twin trap: self-reinforcing, cyclical and clinically insidious.

Among everyday citizens, corruption often begins not with greed, but with aspiration. Newly married couples, and those preparing to marry, increasingly pursue an upscale urban life with modern amenities, better schools, safer neighborhoods, mobility and social prestige. But legitimate income rarely matches those ambitions. As the gap between earnings and aspiration widens, temptation enters quietly. Family expectations add fuel: parents want children to rise, spouses expect dignity signaled through comfort and society rewards display over restraint. When income cannot sustain the life one wants to project, ‘small’ acts of under-the-table convenience become rationalised as necessity. A shortcut becomes a habit — and soon, a culture.

This form of corruption is distinct from bureaupolitigraft — the structured, large-scale graft produced by political-bureaucratic symbiosis. Bureaupolitigraft feeds on power; aspirational corruption feeds on desire. Both drain national integrity — one systemically, the other socially — but together they build the foundations of a profoundly corrupted state.

The coming national election exposes this reality starkly. BNP has nominated 272 candidates, with 28 pending — many of whom are remembered less for service than for scandal, evasion and entitlement. Nominations have quietly transformed from responsibility to investment. Once a nomination is purchased, the office must yield return. Politics imitates venture capital, power becomes an asset class and parliament morphs into a profit hub. Small wonder political neophytes — unqualified even for mid-level civil roles — bid aggressively for candidacy. When office is bought, governance becomes rent-seeking; when power is traded, the public interest is pawned.

Many returnees are sexagenarians and septuagenarians who, in their quinquagenarian prime, presided over the years when Bangladesh earned the ignominy of ranking as the most corrupt nation on earth five times consecutively (2001–2006). Their legacy is not a fading scar — it is the architecture of dysfunction we still occupy. Age is no disqualification, but age without evolution becomes entitlement embalmed in decay. The nation watches with uneasy curiosity: will their return repeat the old script in déjà vu — or will it mark a long-delayed moral awakening?

Recent nomination behavior suggests little has been learned from the July uprising that sent looters fleeing — homeless, disgraced and slipping across borders under cover of night to evade accountability. Bangladesh cannot afford nostalgia for predators who mistake power for inheritance.

Corruption is not merely theft, it is a business model of governance built on extraction. At every civic touchpoint — police clearance, utility connection, land mutation, hospital report, business permit, court affidavit — the citizen pays a toll. Poverty weakens resistance just as corruption strengthens incentive. The poor cannot afford justice; the powerful can purchase impunity. One side submits out of survival, the other abuses out of entitlement, a symbiosis of suffering and plunder that turns rights into privilege and privilege into immunity.

A poverty trap means a child born disadvantaged grows into disadvantage — malnourished, unskilled, unseen except as labour. A corruption trap means a citizen seeking fairness must first negotiate power — pay, plead, or perish. One locks the body; the other locks the future. Worse, corruption drains the very resources needed to break poverty: budgets leak, tenders inflate, loans disappear, bridges crack. Each stolen taka births another generation of cheap political muscle, children who grow into men hired for rallies, protection, or violence. Poverty reproduces vulnerability; corruption reproduces dominion. The twin trap does not merely persist, it regenerates.

The order of reform matters. Poverty cannot be abolished without income, investment, and mobility. Yet investment withers under uncertainty, growth collapses without trust, and trust cannot survive without rule of law. Rule of law cannot exist where corruption governs. Bangladesh must break the corruption trap first; poverty will not fall while bribery remains the price of participation in civic life.

When politics becomes franchise ownership, governance devolves into collection. Ministries convert into private estates, public assets into revenue streams, and the nation runs through intermediaries — brokers, fixers, collectors. Elections may change faces, but systems persist unless incentives change.

The electorate now stands at the edge of a historic decision. Will power return to those who normalised plunder, or move to those with intellectual honesty, institutional discipline and administrative courage? On this choice, it rests whether the twin trap tightens, or fractures.

Democracy is not merely voting; it is stewardship. It is the resolve to say ‘not again.’ Bangladesh has suffered enough under rulers who treated the treasury like inheritance and citizens like collateral. What the nation needs is not just new rulers, but new thinking. True reform requires institutions that outlast personalities. No country has lifted millions from poverty while treating bribery as an operating cost.

Breaking the twin trap requires transformation across three dimensions: politics must move from extraction to service; governance from secrecy to accountability; and the economy from survival to productivity. None is easy, all are indispensable. No society prospers when the honest are punished and the corrupt are promoted; no democracy survives where citizens are valuable only during elections, disposable afterward.

Bangladesh is not at a crossroads, it is in a cul-de-sac, unless an exit is carved through walls built by corrupticians and mortgaged on the backs of the poor. History will not forgive another cycle of returnees recycling ruin. This nation deserves leadership capable of rising above appetite, beyond entitlement and outside the closed circle of past predators.

Corruption impinges from two channels: low-income public servants and the collusion of bureaucrats and politicians. The diagram, instead of explaining a theory, shows a mechanism. Each box flows logically, exposing how deprivation and dysfunction feed each other like two gears locked into mutual rotation. On the left, poverty reproduces itself economically — low income → low savings → low investment → low productivity → low growth → deeper poverty. On the right, corruption reproduces itself institutionally — weak institutions → weak enforcement → corruption → revenue leakage → low investment → low productivity. The diagram shows how poverty and corruption intersect: low income drives corruption, and corruption depresses income and growth. Public discourse often treats them as separate problems, but here they appear as a single braided trap. The two return arrows close the loop like a feedback circuit, showing the cycle repeating indefinitely unless disrupted.

Between poverty and low income, causality is not linear but circular, a chicken-and-egg paradox of development. One may begin with low income and sink into poverty as opportunities contract, savings evaporate, investment shrinks, productivity falls, and growth collapses; or one may be born into poverty itself and inherit deprivation before agency ever arrives. Poverty produces low income, low income deepens poverty, and the loop closes upon itself.

Low income can ignite corruption too. When wages cannot sustain a household, when effort brings dignity but not survival, the line between need and transgression blurs. A clerk demands speed money, a police officer accepts a fee for leniency, a bureaucrat delays service until ‘tea money’ flows — desperation masquerading as discretion. Corruption drains revenue, leakage weakens development, investment falls, productivity declines, growth slows and poverty returns to claim another generation. Two traps, two spirals, braided into one.

Bangladesh can still break free but only if corruption is treated not as culture but as enemy, not as inconvenience but as existential threat.

Dr Abdullah A Dewan is a professor emeritus of economics at Eastern Michigan University, USA.